Concentric Circles: Page Hill Starzinger

David Baker: You are a poet and you are a business woman. You’ve been living since 1980 in the East Village of Manhattan, but before we explore the present, I wonder if you could say a little bit about your origins—your father and mother, your family, your schooling, your beginnings. We are each a community already, aren’t we? Did you, in college, write poems? Did your father’s work in law or political science affect your own sense of yourself or others?

Page Starzinger: I grew up cloistered in a small Vermont town—one general store (Dan & Whit’s), one inn, one post office, four churches—across the river from an Ivy League college (Dartmouth) in the middle of the woods. First grade was a public school in London, but mostly I was in school in Vermont except for three years in high school in Troy, NY (where I remember a hybrid class on poetry/painting, a Patti Smith concert and a semester in Ojai, CA). My father taught political science; my mother drew, etched, fashioned papier mache marionettes, wrote poetry on a little cranberry Olivetti Underwood Lettra 33, tucked in its own leather case.

I spent time studying her books on Arp, Paul Klee, Chagall and other idiosyncratic European modernists who were inspired by dream imagery, and other surrealist elements, “collaging” together different crazy-patch subjects.

We would visit Boston, and Mom took us to the Museum of Fine Arts, and to Design Research on Brattle Street in Cambridge, which was opened by a former partner of the modernist Walter Gropius—a landmark store that mixed Noguchi lamps with no-name Bolivian sweaters, and influenced the founders of Crate & Barrel and Design Within Reach. Finally, college at WesleyanUniversity, which has a polyphonic arts scene. I didn’t write any poetry there; I was quite lost.

DB: Can you give me a bit of a collage poem, one of your earlier ones?

PS: Here are the first two sections of a five-part poem that focuses on deviations of power that infest and deteriorate community and culture, often in ironic and hilarious ways that you just couldn’t make up. The Ivory Coast, a producer of lubricants, builds a full-size copy of a St Peter’s, one of the holiest Catholic sites.

Alpha Protein

1.

In the world of gift

you can’t have your cake

unless you eat it. —Hyde)

Helix

a curve on any

developable surface

screw

as long as preload

is not exceeded,

bolts will not come loose

2.

ABIDJAN, Ivory Coast, August 19—

Toxic cocktail laced with

dumped in

by Greek-owned tanker Panamanian flag

leased by the London branch of

a Swiss with a fiscal in

high concentrations you can no longer smell

because it paralyzes

your nervous system

this, in a republic

boasting a full-sized replica of St Peter’s in Rome

consecrated by the Pope

gift bestowed but At present, travel

is ill-advised. Police can be excitable

armed elements are

under influence of Keys to the economy:

oil industry and

active chemical industry specializing in lubricants

DB: That’s so beautifully complex. You integrate the pieces into your collage-poem but also expose them as pieces. The phrasing is fractured in places, interwoven in places. It’s like looking at a three-dimensional version of language where politics and etymology mix, and where the personal and cultural mix.

After college you moved to Manhattan, where you began a career in fashion and editing; you worked for 12 years with Vogue magazine, and I know you traveled. What about those years and that work has stayed with you?

PS: My grandmother sent me a subscription to WWD, the daily fashion rag-trade newspaper, when I was a teenager, and my mother always got Vogue. So when a friend’s father, the writer William Zinsser (On Writing Well), recommended applying for a job at Conde Nast (which owns Vogue), I was hopeful, but not at all sure what I was in for. My first job was fact checking the Fashion Copy Editor’s work, and this taught me focus, to a certain extent, but what I really enjoyed was writing captions for the big center-of-the-magazine fashion spreads photographed by everyone from Helmut Newton to Patrick Demarchelier: I liked being absorbed in the visuals, decoding the conversation and messaging, and jumping from one story to the next.

Here are the first two parts of a three-section poem that speaks about emotional paralysis through visual cues, and referencing the work of several artists: Louise Nevelson, who resurrected discarded and cast-off objects—street remnants and scraps—into heavenly assemblages; Sol Lewitt whose deceptively simple line drawings are designed to be perishable—created, erased, and recreated elsewhere based on guidelines that can be executed by anyone. “The man” is Derrida.

Terroir

1. Unshelter

I can’t open the door and even if I draw a doormat

on the floor, I can’t break out. Keep low: underneath,

I see the sill, my slice of. Thin enough for a Cantor’s turtle

—no shell—which spends its life motionless, buried

in sand, surfacing twice a day for one breath each. I

could whittle myself into fiction. Sol

Lewitt’s breakthrough Wall Drawings—sketched

from ceiling to floor—like modern cave art

—are made to be painted over. What is

left behind? Lewitt sketched diagrams. The turtle lays eggs. Me?—

the Chinese would say, swallow nesting on a curtain.

In L.A.: set of box springs

on freeway shoulder. Man says, unshelter oneself.

Don’t limit oneself to words when there are sentences.

2. Cast-Off

The hummingbird sings outside your office

—little quick chirps—

like a chipmunk. This delights you.

Louise Nevelson, in Dawn’s Wedding Feast, 1959

painted stacked wooden crates filled with street finds—

shutters, hubs, chess pieces—all-white. Absolved. And you,

who see: the jambs, the archvolt, the panic bar,

the peephole. You put your fingers on my right arm and said

I’ll find you.

DB: After Vogue you worked in a number of other positions, but notably for Estee Lauder and now for more than a decade with Aveda. You are the creative director for copy at Aveda. I think that means you are the head writer and the director of the other writers. Does that work affect your poems?

PS: Aveda is a beauty company with a mission to care for the world we live in. They are committed to doing this in a variety of ways—including tracing ingredients back to each farm and community to ensure integrity of formulation and fair treatment of workers. So there are real stories about community to investigate and communicate—usually from far-flung countries, Morocco, Australia, Brazil. On January 16th, I’m traveling to tiny villages in Nepal to see our partnership with indigenous peoples in forest communities who are hand crafting our gift paper from sustainable lokta bark. Around Annapurna, these locations are some of the poorest in the world.

DB: It will be fascinating to see how your trip to Nepal may affect your poems, or even show up in your poems, don’t you think? But you didn’t say much about how your work at Aveda has affected your poems. Or maybe it doesn’t?

PS: Writing about indigenous and local communities—suffused with ancient, rural rituals—for over ten years now for Aveda, the company keeps me focused on “the other.” We source our argan oil—for skin care—from Morocco, and that was a touch point for this poem:

New York Pastoral

I occupy the periphery

(somewhere to watch)—

teetering on long thin thorny limbs

like Tamri goats who scamper up Argan trees for leaves and nuts

stripping them bare

: a border of relief, this; the guards deliver

take-out Chinese or drugstore supplies;

they live places

I don’t know; they seem to come out of the orange fog

hanging

over the city. I wish you were around

the corner; closer, I mean,

knowing there is only

so much closeness one can take—to be happy:

but, if you lived here, you could catch

snow flakes tumbling through ceiling grates

in subway tunnels:

so odd and white in the darkness

and you could hear masses of birds singing: so few trees

clustered at the concrete edge. Things are more intense

on the perimeter

: like longing, or a tree. I love

this place so, but you aren’t here, and so

something’s always missing

although I talk to you all the time. Do you hear me?

Today, I tell you that the wood and nuts of the Argan tree

are burnt for cooking

deep roots prevent erosion,

and the Sahara is creeping nearer. Old love

is about wanting someone else

to be happy. I want you near me.

Argania spinosa?

Evergreen.

DB: You started writing poems again, after more than twenty years of silence, around 2004. What inspired or prompted your return to poetry? What were you looking for? And what were those early poems like? Short and terse? Or were they, like your recent poems, sometimes longer and polyphonic?

PS: I realized I had succumbed to insecurities, which didn’t please me, and I also started having a small sense of fatality. It was Louis Auchincloss who said, “A man can spend his whole existence never learning the simple lesson that he has only one life and that if he fails to do what he wants with it, nobody else really cares.” The poems were caught in my throat, very small and spare, yes, terse. I could barely get them out. Then I chiseled them down to bone.

DB: Would you show me a chiseled one—again, one of the earlier ones where you started this technique?

PS:

Cutting Board

I did not always recognize the pleasure—

but it is unavoidable:

the slice. The way he bends into it.

Briefly. Then leaves.

I am full of wanting.

The sheer physicality of it

obliterates

questions: you know what they are.

I shall not miss him is a lie.

DB: I see what you mean. It is lean and tight. I like its clarities, but compared to your newer poems it’s also more blunted, less chewy or elliptical or layered.

So let’s talk about your poems now. You have been writing with real seriousness for the past five years, and your poems have appeared in many important magazines, especially magazines that are noted for their appreciation of innovative writers—like Volt, Conduit, the Denver Quarterly, Fence, and others. Could you talk a little about your process of writing a poem? I know it is unusual, and complex, and seems to require a sense of plurality, a kind of communal imagination. But talk about your process. Where does an idea come from? How do you prepare to write a poem?

PS: I clip every day—even in Blaine, Minnesota, where I spend two weeks every month for Aveda, I drive half an hour to get a New York Times. That paper, and the New York Review of Books. Whatever catches my eye I save, underline, investigate further online. I store these in vanilla folders, and date them. They hang together in themes. They spark ideas, as well as visits to galleries and museums, which feed into the general themes, or initiate subjects. Sometimes I catch myself thinking the clipping won’t be of interest—but if I edit too much I find the folders then aren’t that surprising. It’s really following my instincts and trusting that there is something there.

DB: You clip like a researcher. I’d like to see some of your clippings, and a list of what you clip, and a little discussion of why you chose those pieces.

PS: December 30, 2010 from NY Times:

- Mexico City Journal: Bare-Bones Approach Lets a City Embrace Winter

. . . His home, like nearly every building in this megalopolis of 20 million people, has no central heating. And because concrete is the dominant building material, winter here means a indoor existence with temperatures not far from freezing. . . Deep in the country’s Aztec roots, there is admiration for submitting to the elements. . . “We’re always struggling with what Mexico really is,” Mr. Gallo said. ”It’s a slight disconnect between the image and the reality of living in a city that has a mountain climate.” . .For many Mexicans, though, the lack of heat has less to do with protecting the environment than with accepting it. Mr. Gallo said that while Americans try to fix the cold, Mexicans rely on fatalism as a means of coping, a sense “that this is how it’s supposed to be.” Mr Sandoval offered another take: “The weather is something you participate in,” he said. “It’s something you’re part of.” Mr. Aridjis, the poet, agreed. During a tour of his book-filled, ice-box of a home, he said he sometimes found ice crystals in the shower, but he also fondly recalled a rhythm of writing by temperature. He would work for several hours until the chill consumed him, then he would step outside to soak in the warming rays of a winter sun.”

Of interest here is submission, acceptance, habit, disconnect between image and reality, cultural and philosophical differences in relating to weather, the concept of participation with a natural element. I struggle with accepting what “is,” and sitting with it—especially internal weather ie emotions; understanding and appreciating reality rather than dream worlds. I attempt to substitute new habits for old as rituals are either/both comfort and crutch. Participating in life—rather than passively allowing something to unfold—being engaged rather than invisible—is another subject.

- New Look for Mecca: Gargantuan and Gaudy.

JIDDA, Saudi Arabia – It is an architectural absurdity. Just south of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, the Muslim world’s holiest site, a kitsch rendition of London’s Big Ben is nearing completion. Called the Royal Mecca Clock Tower, it will be one of the tallest buildings in the world, the centerpiece of a complex that is housing a gargantuan shopping mall, an 800-room hotel and a prayer hall for several thousand people. . .decorated with Arabic inscriptions and topped by a crescent-shape spire in what feels like a cynical nod to Islam’s architectural past. To make room for it, the Saudi government bulldozed an 18th-century Ottoman fortress and the hill it stood on. . .The closer to the mosque, the more expensive the apartments.…dividing the holy city of Mecca—and the pilgrimage experience—along highly visible class lines, with the rich sealed inside exclusive air-conditioned high-rises encircling the Grand Mosque, and the poor pushed increasingly to the periphery. . . deforming what was by all accounts a fairly diverse and unstratified city. . . . Like the luxury boxes that encircle most sports stadiums, the apartments will allow the wealthy to peer directly down at the main event from the comfort of their suites without having to mix with the ordinary rabble. . . Many people told me that the intensity of the experience of standing in the mosque’s courtyard has a lot to do with its relationship to the surrounding mountains. Most of these represent sacred sites in their own right and their looming presence imbues the space with a powerful sense of intimacy. But that experience, too, is certain to be lessened with the addition of each new tower, which blots out another part of the view.

This one seems to me a counterpoint to the Mexico City article, hermetically sealing off rather than embracing the elements—of nature and spirit; the destructive capabilities of religion and faith dovetailing with governmental purpose to disrupt cultural fabric. I struggle with hibernating or retreating so I tend to notice other instances. I know that many people find calm and clarity in religious belief, and I am also aware of how it operates as a powerhouse, like a corporation, and undermines the equity it builds.

DB: In her new book, Unoriginal Genius, Marjorie Perloff discusses the “unoriginal” language of recent experimental poetry, language taken from the internet, from citations, all the prior language that makes overt, or self-conscious, the fact that all language is inheritance, always already having been used before our use. There is no original utterance. Would you show a poem with pieces of your clippings, and talk about how you execute such things?

PS: In talking with my boyfriend about living together, I struggled with what to do, what loss. Falling, it seemed sometimes. I explored my folders of clips and pulled what resonated with this contradictory feeling of ecstasy, fear and flight. First, a New York Times article about how a river’s waterfall allows the current to return to a normal flow, correcting itself in order to erase itself. Falls are paradoxical places. Here things fall apart, literally shattered, and then righted, restored, albeit differently, beautifully. The process is powerful, you feel present. I researched Victoria Falls, beginning with Wikipedia, and discovered how it has a black basalt edge, the river plummets in a single vertical drop to create the largest falls in the world (if not the highest or widest). The African name translates as “the smoke that thunders.” An article about Leonardo de Vinci, the ingenious inventor, painter, and engineer spoke about how he wrote right to left, looking at things from a different perch. Sublime. I dug into Oxford dictionary to root around in the definition. All these pieces worked together in the first two sections of the poem. In other sections, I mixed in pieces of conversation.

Lyms of

Rim of light. Crawling to the black

basalt edge. I’ll say the wrong

thing and move in with him. Falls are the river’s way

of getting back to normal. Simultaneously a mistake

and correction: in order to erase itself. At the rift between

the water’s force and its path. (The physical industry of it.)

What causes the smoke to rise so high

out of water, the Kololo asked. (About Victoria.) So

Leonardo wrote backwards, right to left

using the left hand without punctuation. So

limb means border

all be but lyms of blissidnes

when you face limits

rip them

off

Sub up to = limen lintel

Hee on the wings of cherub rode

towering. arch. and

Errant.

(in quest of

, or

poet.

9. Astray,

b. as pred.?

Quantum pop. Loss

DB: Can you say more about word origins? About your interest in word evolution? That’s a central motif in your new poems. The meaning of your poems seems somehow about how poems mean.

PS: I’m interested in the substrates and shallows and coves that lie under or behind. I probably would like spelunking, if I didn’t feel claustrophobic. Ruins of towns—or investigations of fantasies like Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities—interest me as well. You can’t really dig around in these, unless you are an archaeologist or geologist or biographer/critic. Oxford English Dictionary makes the histories, many obsolete, immediate—unfolding each word on the page back in time through their conflicting and dovetailing evolutions. Their new Thesaurus traces the meanings back. I like focusing small, on one word; within, flies out a macrocosm of life.

DB: I see how you find clippings, phrases, information. But now, how do you find the form of your poems? They are frequently splayed and opened, rather than more traditionally formal. I see, as you mentioned earlier, how some of your formal imagination derives from the visual arts. Can you show part of a poem and talk about the formal decisions?

PS: My first answer is that the form of my poem develops instinctively. It is a physical reaction to the subject and emotion, not intellectualized. My second answer is that there is usually a repeated grid at work underneath, a matter of containment—of the odd, multifaceted pieces. In earlier poems it was evident—numbered couplets—as in this poem based on the work of painter Robert Ryman, who also establishes order with a grid:

Series #22 (white)

Oil and gesso on canvas Robert Ryman, 2004

1.

As if it were still the 17th century, when conscious

just entered the English language, meaning secret and shameful:

2.

the whitewash of brushstrokes over black. It was like erasing

to put white over it, Ryman says, but gives no hint of what—

3.

everything we have words for is dead.

No wonder, Nietzche said, I forget; so it repeats, like a series

4.

of couplets: In Hebrew darkness is not unrelated to childlessness.

Alone: this is not a choice. It’s a compulsion. Last night . . . .

Most recently the forms of organization—of controlling the chaos—are more complicated and organic (even eaten away)—maybe “fractal” is the right word. A new poem has divided itself into four sections of ten lines each, holey and ragged like an old sock. The line breaks and puddles of erasure occur naturally like a crack opens along a fault line or a spill of bleach whitens darkness.

DB: That’s fascinating. I know it’s not finished, but would you show me a little of this new poem, still in progress, to show to fractal quality?

PS:

Who’s

there? Me. But some bifurcation early on

makes the sense of

yours truly

unseen, indistinct, fleeting. . .

foremelting

(don’t you like that: 1606 antecedent for

invisible).

Can you challenge that pattern?

If I’m paying you all the money, can’t you fix it.

Meanwhile, in Delhi, 60% live

in makeshift homes

without clean water.

In Japan,

the Paper Church and Curtain House

are loved.

Anopticall.

1598. Obs. Not in the field of vision.

Reminds me of apocryphal.

It’s being able to claim what you need

DB: Which visual artists mean the most to you? Why? What do you take from them into your own poems?

PS: Visual artists that excavate strata, recover the lost and overlooked, and recompose them, often within boxes or grids that contain fear and fantasy. Joseph Cornell, Louise Nevelson, and many outsiders like Henry Darger. Also performance artists like Cuban-American Ana Mendieta, who especially early on, focused on violence against the female body. She typically carved her imprint into sand or mud or meadow, and maybe this is part of the inspiration for the form of my poetry. Sigmar Polke applies clumps or droplets of ancient substances or mass-produced fabrics—soaked in lacquer—to the canvases in juxtaposition with sketched figures. His fingerprints might be visible through a film of deliberately applied dust. He applies arsenic or lavender oil—precious or toxic substances—that alchemically change color or texture; violet turns gold as it dries in the sun. He works with materials that shine or sheen or shimmer: “I am trying to create another light, one that comes from reflective surfaces. Like celestial light, it gives the indication of new supernatural things.” I like this quote best: “A finished painting is an impression of millions of impressions.”

DB: Is that how you think of your poems—as a verbal impression of millions of impressions? Certainly that fits with your technique of collage and clippings. So how do your experiences in fashion and business—your work with Vogue or Aveda—provide impressions for your poems?

PS: I don’t find that my work at Vogue or Aveda animates my poetry because the use of language, and thinking, is very different. I try to distinguish between the two: focusing on editing at work, and writing at home. Even though Aveda is non-corporate in some ways, it may heighten my interest in the ways in which power can be a positive—and negative—force.

DB: You write about power in your poems, no doubt. Does poetry have a power of its own? Is it powerless or powerful, or is that irrelevant?

PS: I think that poetry can be extraordinarily powerful; it slips in between thoughts to upend the status quo. I have heard Merwin say that poetry is part of all of us, children sing when they are young, and chant; yet it is pretty much wrung out of us. I wish, too, that it had more support, in school, say, to begin with. I think it is a great opportunity for restoring equanimity and kindness.

DB: Many poets today find their vocations inside the academy. You often take part in workshops and conferences, and you give readings, but you are more outside the field than many of your colleagues. Still, you’re in good company. I think of T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, or more recently Alice Notley or Amy Clampitt, major poets who were or are not part of an academic setting. How does it feel to you to be “outside,” or do you think about that?

PS: Concentric circles form a target, and I often feel like I should be working my way inside to some goal or point that I’m missing. On the other hand, being outside is familiar, and crisscrossed with worn paths that form offbeat trajectories with surprising views. I’m sometimes afraid that absorbing too much of a well-traveled approach could be stifling. There are so many talented teachers to learn from in academia—I’d like to work with a hand-picked group: it would be fun to organize your own private masters’ program.

DB: The poems you’ve included here so far have been culturally wide, their subjects ranging from politics to language itself. How about things more close to home? Do you use collage or clipping techniques even in your more personal poems?

PS: Yes, very much so. Here’s a love poem, collaged with bits from a conversation with a friend, and a newspaper account of the celebration—and giddiness—after Hamas militants blew holes in the corrugated-iron border fence at Rafah in January 2008, after a long blockade by Israel.

Complicit

There’s the village my friend calls

un lieu-dit or also called place,

a village without administration,

that’s us, you and me:

no boundaries. Think how

Hamas blew a hole in the wall dividing

Egypt from Gaza, so donkeys and bicycles

could finally cart back bags of flour, cases of Coca-cola,

chocolate and antacid. This is an opening,

love. It calls for defiance and every

last stubborn cell of yours

is up for the fight—that’s what I think. And you?

I know you like the tea kettle just so

on the burner. Here, look: Ala Shawa

and his wife, Hana, walking through the dirt

into Egypt, her hair fashionably streaked.

Adel al-Mighraky, smoking a Malimbo,

We were like birds in a cage. This is giddiness,

and mayhem. Don’t think about it too hard.

And please don’t seal the breach.

DB: Do you think you have a community or company of fellow artists? How do you perceive the community of poets? Is poetry communal, at heart, or solitary?

PS: For me, poetry is solitary; it’s always surprising to me to find community when I am reading or visiting poets or taking workshops. I can only say good things about the people I meet in travels or at Bread Loaf, Kenyon Review Workshops, and Provincetown Fine Art Center. They are passionate and supportive and talented—and they’ll challenge you, and help you grow, if you ask for it. Their kindness is truly remarkable.

DB: Poetry is solitary, but language is communal. How do you see your poems extending into the future? What connections would you like to make with your poems?

PS: I would like my poetry to mean something for someone, or some people. That would be a great gift.

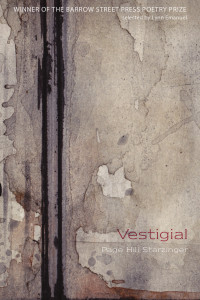

Page Hill Starzinger lives in New York City. Her first full-length poetry book, Vestigial, selected by Lynn Emanuel to win the Barrow Street Book Prize, was published in Fall 2013. Her chapbook, Unshelter, selected by Mary Jo Bang as winner of the Noemi contest, was published in 2009. Her poem, “Series #22 (white),” was chosen by Tomaz Salamun for a broadside created by The Center for Book Arts, NYC, in 2008. Her poems have appeared in Colorado Review, Fence, Kenyon Review, Pleiades, Volt, and many others. She is a Peter Taylor Fellow at the Kenyon Review Writers Workshops 2014. In 2013, Page was the Special Guest at the Frost Place Poetry Seminar.

David Baker is the author 14 books of poetry and prose including Midwest Eclogue (W W Norton & Co Inc. 2007), Treatise on Touch (Arc Publications, 2007) , and Never-Ending Birds (W. W. Norton, 2009) winner of the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Prize in 2011. His latest work Talk Poetry: Poems and Interviews with Nine American Poets is out from The University of Arkansas Press (2012). He has been awarded fellowships and grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Poetry Society of America, Ohio Arts Council, Society of Midland Authors, and others. He has a PhD in English from the University of Utah and has taught at Kenyon College, the Ohio State University, and the University of Michigan. He currently holds the Thomas B. Fordham Chair of Creative Writing at Denison University, in Granville, Ohio. He is the poetry editor of Kenyon Review